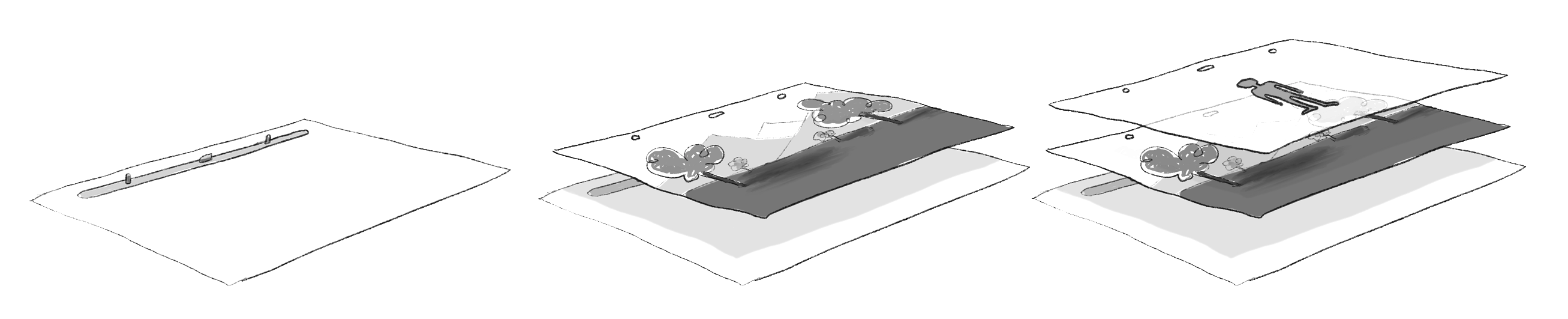

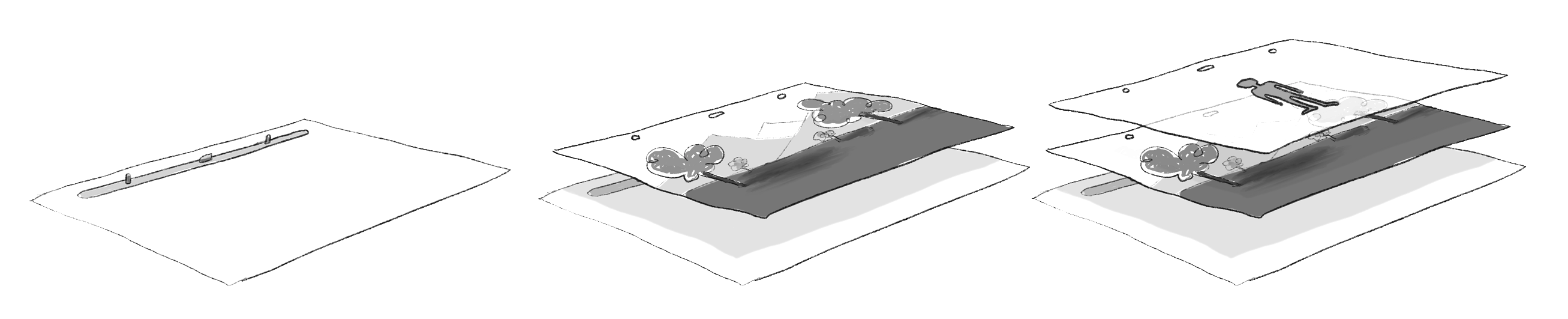

‘Cels’ (named originally due to their being made from celluloid, though eventually this came to be replaced by cellulose acetate, a less volatile material) are thin, transparent sheets upon which traditional drawn animation sequences would be translated by teams of painters and inkers, eventually producing opaque cartoon characters which could be layered on top of painted backgrounds to produce a complete scene, or cel setup. Each individual setup would then be photographed and sequenced according to detailed shooting specifications, creating complex runs of movement and story which occur within a comprehensive cartoon ‘world.’

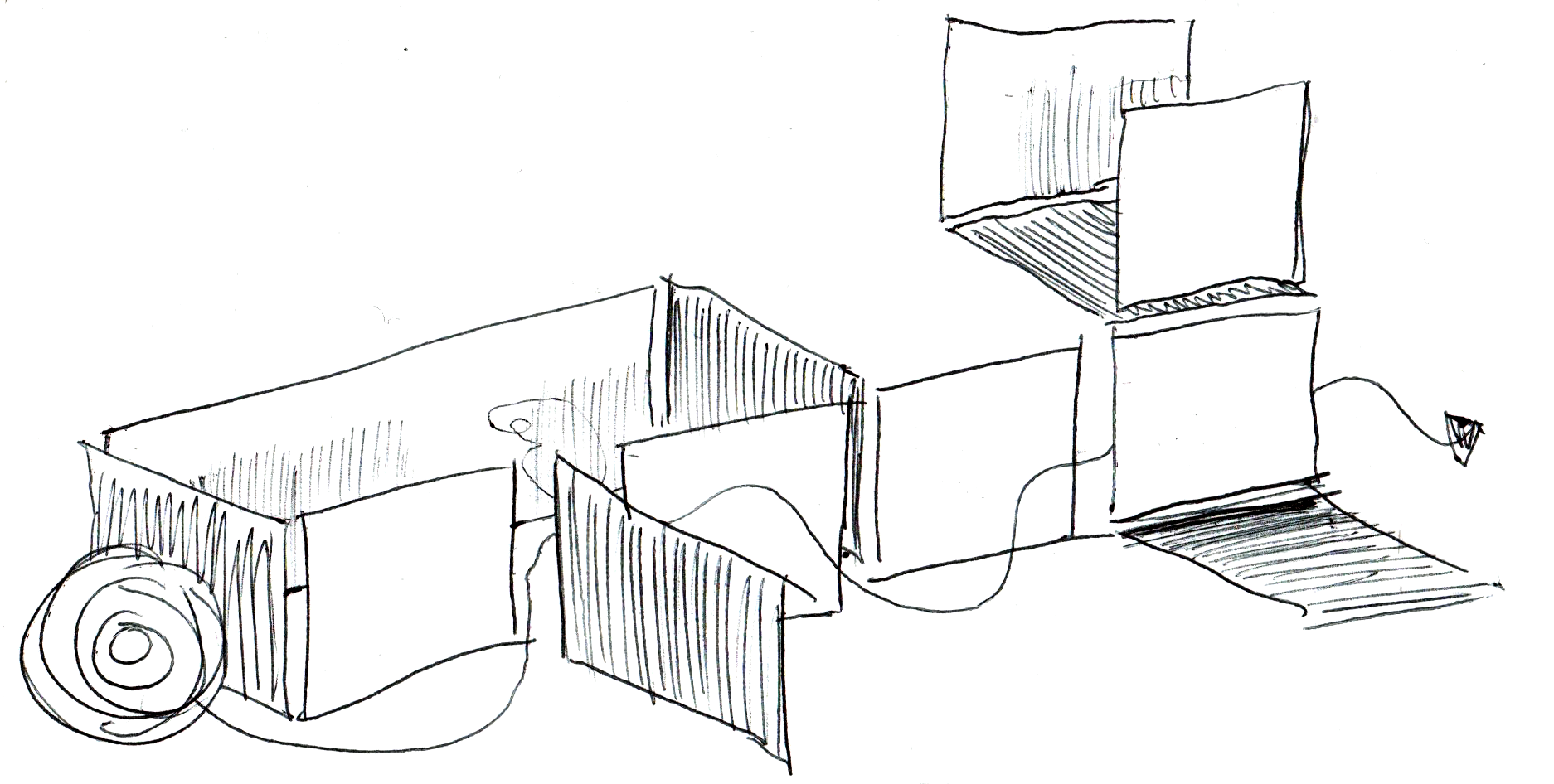

These backgrounds are, ultimately, what house the animated characters. That is to say, the backgrounds come to constitute the place in which the characters ‘live.’ Donald Crafton in his book Shadow of a Mouse: Performance, Belief and World-making in Animation, states that “Performers, even toons, must have a time and place in which to exist, an environment in which to move, a place that surrounds and restrains their behaviour.” In one respect this is what is meant by the ‘world’ of animated cartoons; i.e. the scenes and settings in which the action takes place. However, in many ways the internal logic of the cartoon ‘world’ – if we were to picture the relationships between the individual background images spatially – would probably look less like a ‘world’ and more like a house. Constructed from a finite set of paintings, each of which is planned and constructed in advance, the individual environments exist simultaneously and, at the crucial moment of photographic sequencing, come to form a linked set of ‘rooms’ which the characters move within and between. To get from one scene to the next, there is no need to journey through the ‘world’ to get there; you simply step through the doorway of the cut.

In his essay ‘Plasmatic Pitches, Temporal Tracks and Conceptual Courts: The Landscapes of Animated Sport’, Paul Wells argues for a new approach to understanding animated space. Initially writing in relation to the sparse, ‘selective’ stage design of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (1953) and to Kenneth Clark’s focus on the peripheral elements of ‘great’ artworks in his 1938 book One Hundred Details from Pictures in the National Gallery, Wells provides these examples in order to demonstrate the ways in which other disciplines engage with ideas of constructed space. He writes that, in animation theory, this “re-positioning of the gaze as a more holistic and inclusive apprehension of the literal choices in making the image […] is important because all aspects of the mise-en-scène are specifically chosen and may have a dramatic and symbolic function.” He continues, emphasising the role of function:

The landscape here is not merely a location that is chosen and recorded, but a space that is deliberately composed and constructed, and populated by elements – central and peripheral, foreground and background – that potentially work as ‘characters’, or more commonly, in helping to define them.

Shamus Culhane, in his book Animation from Script to Screen, writes that in cel animation processes “the action guides the layout artist into composing a scene rather than a background being drawn and the action of the characters superimposed onto it.” The backgrounds are painterly landscapes which are composed specifically and deliberately, with reference to an already existing spatial schema; they are created as an incomplete aspect of a final whole in order to fulfil a purpose which is external to them. Empty spaces are left in the layout of each background in order to facilitate optimal readability of the foregrounded animated action. Culhane writes that, primarily, the reason for doing this is “to prevent a common mistake: drawing a character whose nose rests on the vertical line of a door in the distance; or placing the head in such a position that it looks as if it is wearing a flowerpot or some other object in the background”. This careful consideration for purpose, beyond or regardless of the aesthetic qualities of the paintings themselves, creates within them – when viewed alone, as they were originally designed – a distinct visual language of prioritised negative space. When paired with the cels they were designed to house, the backgrounds lose this sense of emptiness; the ‘world’ which the team of animators, inkers, painters, background and layout artists, directors, story writers, and voice actors have been working to conjure is suddenly made whole, and we are invited to enter into it, conditional to our acceptance of, and belief in, the internal world which we come to inhabit, temporarily.