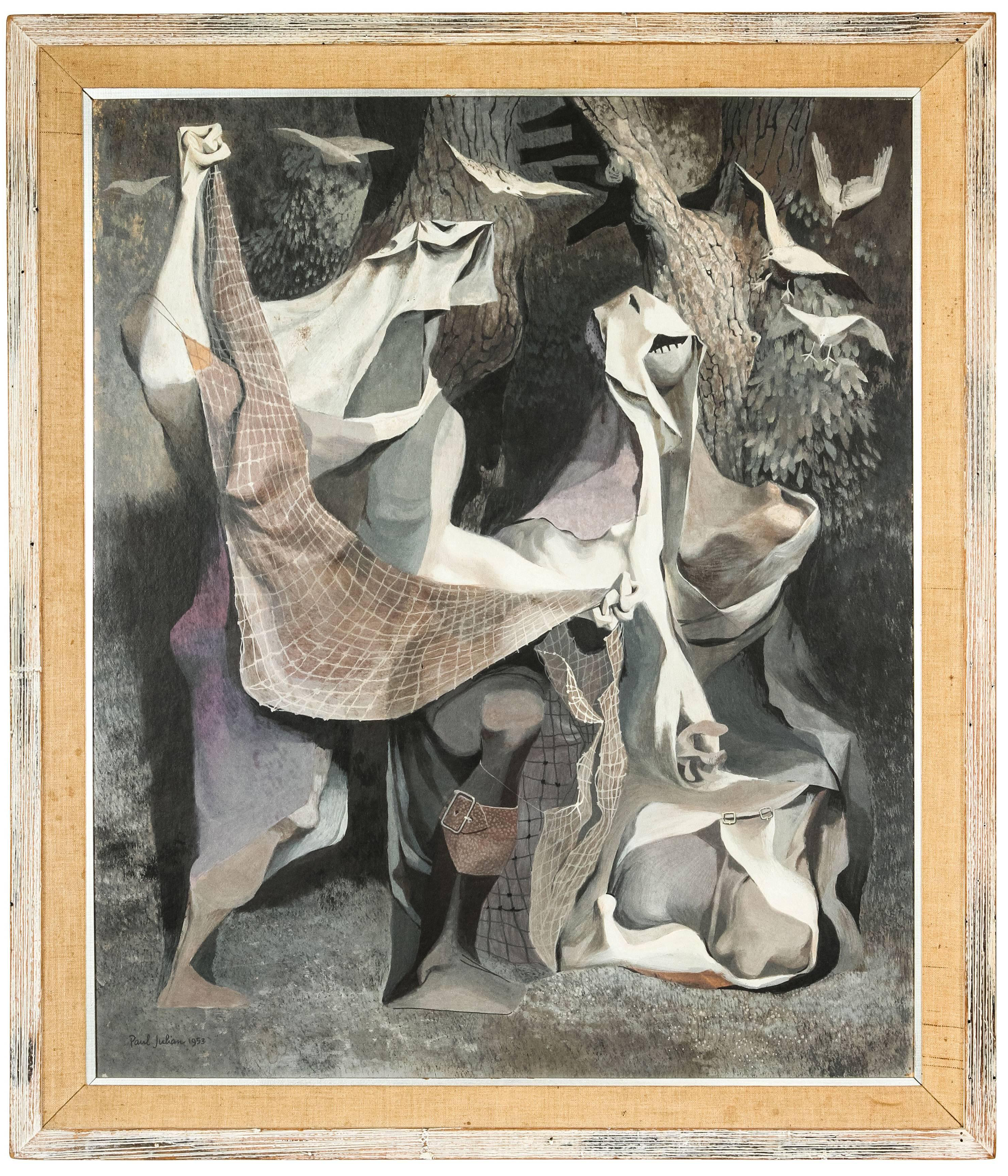

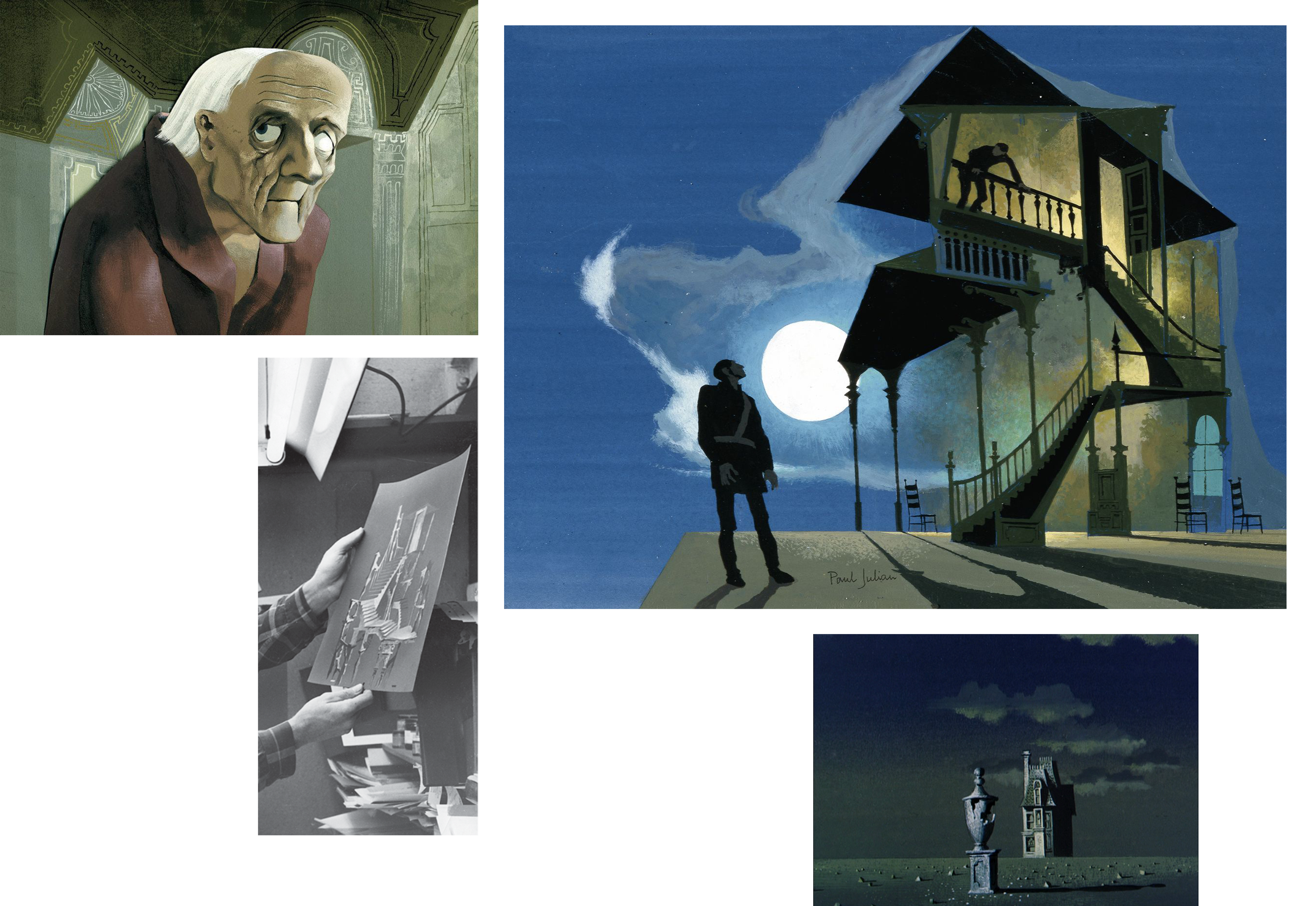

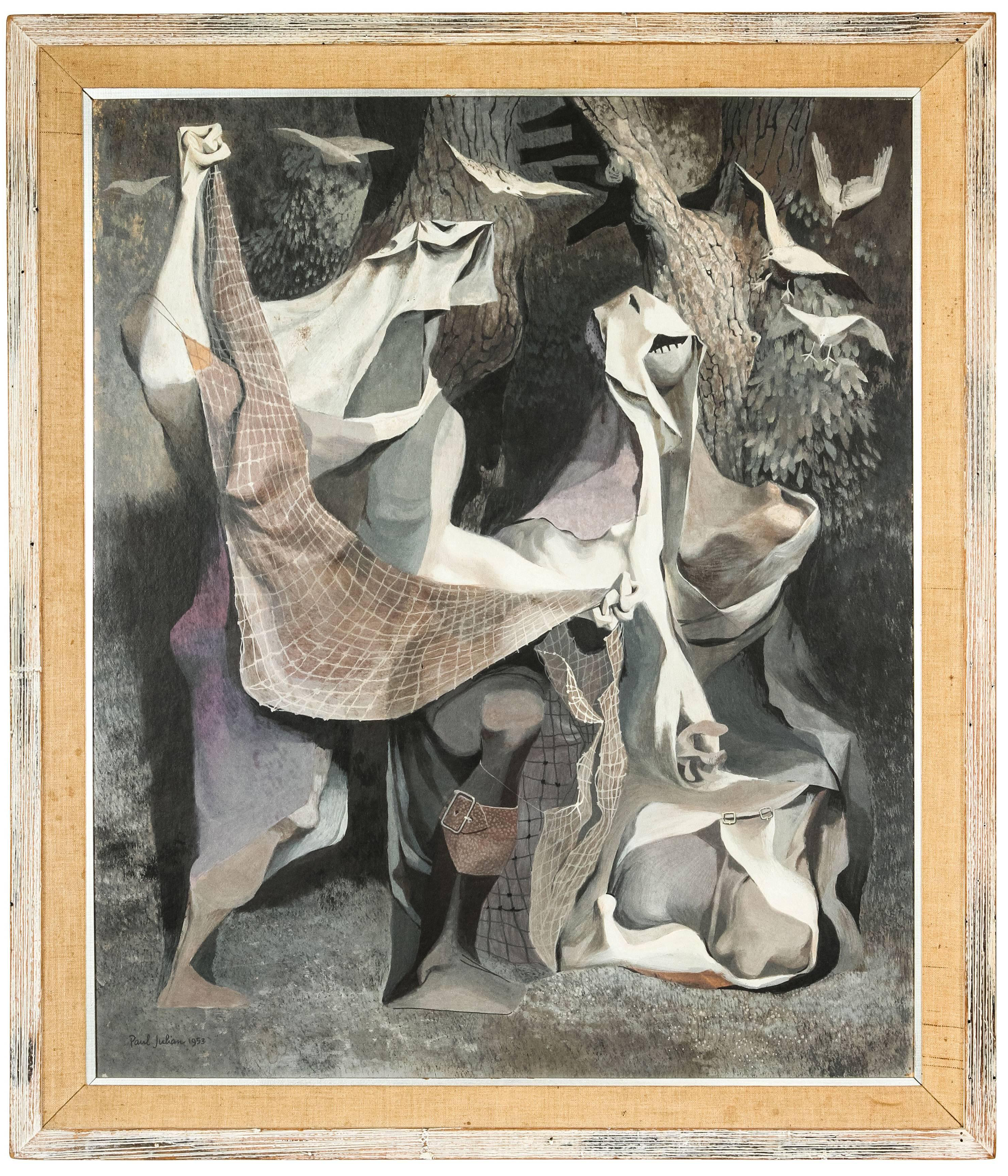

After phasing out of Warner Brothers, Julian’s painting practice expanded outwards and away from the tightly executed yet slightly cartoonish realism which had come to comprise the vast majority of his output within animation. Spurred on in part by the level of freedom afforded to him by the UPA model and their willingness to experiment with background design, Julian would lean into the evolving ‘cartoon modern’ aesthetic and contribute his talents to some of the most visually distinctive and highly lauded cartoons of the era, including 1953’s Oscar nominated The Tell-Tale Heart, the bulk of which is constructed solely from Julian’s paintings. According to Adam Abraham, author of one of the most comprehensive written histories of UPA, Julian created “around 75 percent of the layout drawings and painted every background” for the film. Stephen Bosustow, the head of UPA during Julian’s time there and producer of almost every one of their major cartoons, declared that the film was “Paul Julian’s masterpiece.”

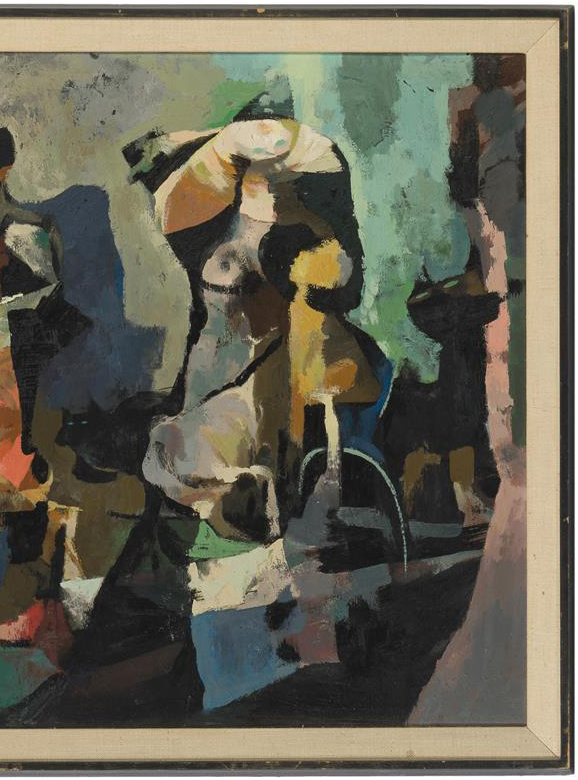

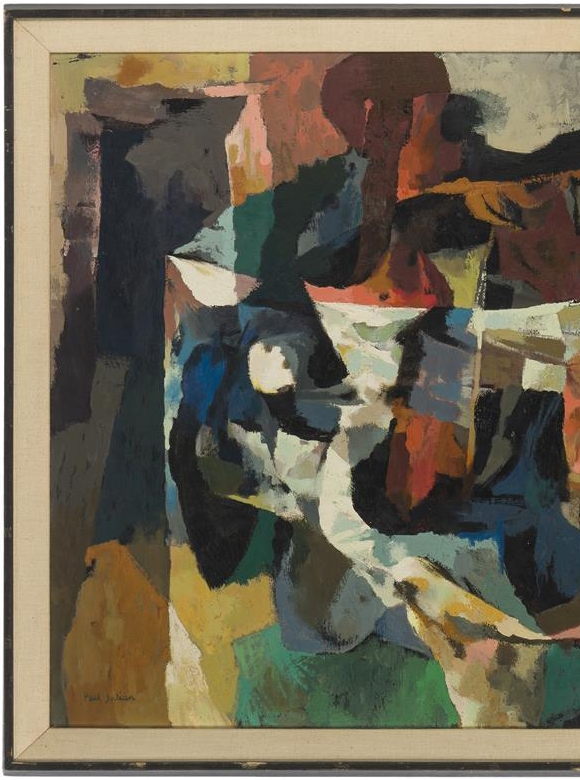

The film features very little character animation; often, figures are painted fully rendered into the backgrounds themselves, with audible dialogue coming from unmoving mouths. As Abraham describes, the motion of The Tell-Tale Heart came instead from “a series of lingering camera moves and languorous dissolves over Paul Julian’s decayed, distressed, and disoriented paintings. The minimalist animation, contributed by Pat Matthews, is secondary to the layouts.” The material separation of back- and foreground which had become so intrinsic to Julian’s working artistry was, for a moment, suspended; the strict constructional barriers surrounding his animation work began to bend and break, and these shifts simultaneously became visible in his personal painting practice, where ongoing experiments in style and form had already been developing through small-scale paintings placed into animation interiors.

Paul can use both hands the same, you know. I know this because sometimes he swaps when he’s painting me up. One gets tired, the other one takes over. Doesn’t miss a detail though; puts it down just as nice. He can write with them both too. Sentences and everything. If someone asks the right way, he’ll do this trick where he takes two pens, one in each hand, and he’ll start writing a sentence from both ends. He knows how to look at space properly, you see. All the distances and the lines and everything, he starts off and nobody thinks it’ll work and then he meets it all up perfectly in the middle of the page. Paul’s always one step behind and one step ahead.