Building from Derrida’s writing in Specters of Marx, much of my previous research has been an effort towards the development of an explicitly hauntological methodology. Through engaging with the writings of Jacques Derrida and Roland Barthes (among many others), this methodology has come to compose three main aspects, which I will list and then briefly develop.

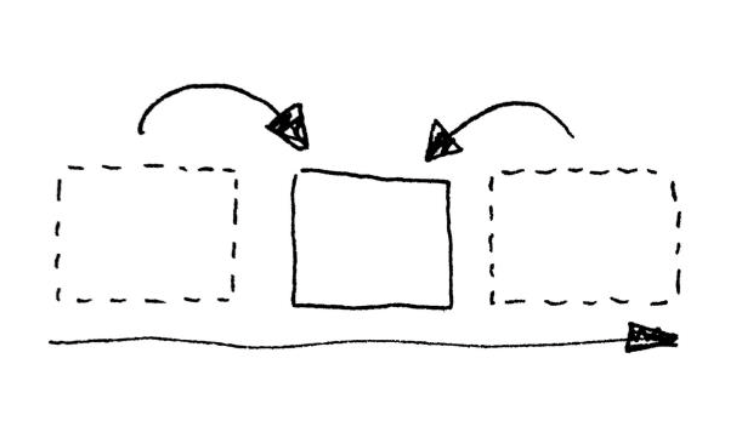

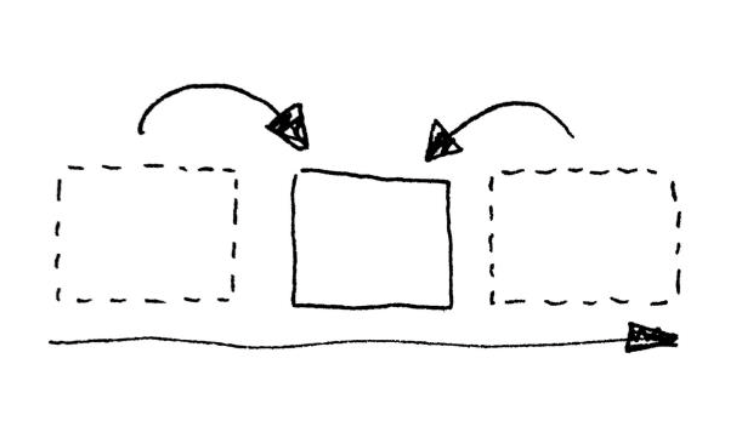

The apertura, i.e. a hole or opening which, despite consisting of only absence, indicates a point of potential development toward new knowledge, was developed in line with Barthes’ (and Derrida’s) description of the punctum as a moment of ‘puncture,’ of an instantaneous, subjective, and ultimately inarticulable relation between a photograph and its viewer. The apertura is a simultaneously subjective and objective point of hauntological intrigue – as in, we act on it through interpretation, and it acts on us by drawing us in, by prompting us. It leads the viewer to more closely engage with the point of absence which the apertura comes to signify. It provokes in us a sense of spatial physicality – it becomes not just something but somewhere. From within this point of situated, hauntological clarity, we can then turn outward and apply the second main aspect of the hauntological methodology: the temporal and spatial hauntological frameworks. The temporal framework posits that each instant in time is ‘haunted’ by every other instant. Our knowledge of the present is always informed by the memory of what came before and the expectation of what will happen next, turning ‘linear’ time into an overlapping nexus of hauntological relation and reference. This draws from Derrida’s notion of trace, which Martin Hägglund elaborates on in his book Radical Atheism: Derrida and the Time of Life:

The structure of the trace follows from the constitution of time, which makes it impossible for anything to be present in itself. Every now passes away as soon as it comes to be and must therefore be inscribed as a trace in order to be at all. The trace enables the past to be retained, since it is characterized by the ability to remain in spite of temporal succession.

The trace of the future works in a similar way; the anticipation of what is yet-to-come influences our behaviour and actions, despite its being inherently, and essentially, not yet.

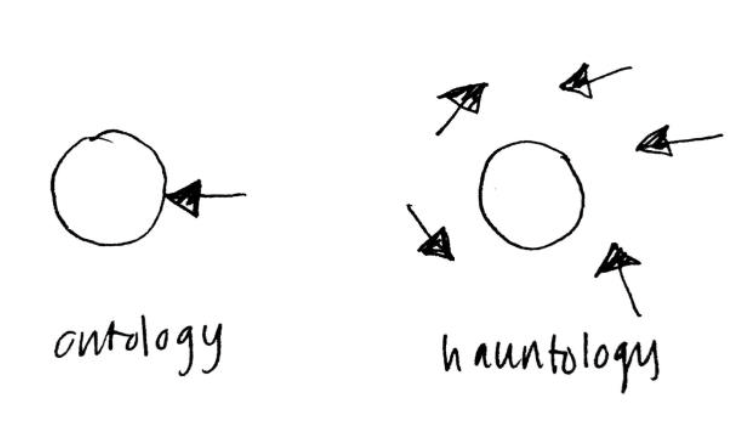

With continued reference to the trace and also to the similar Derridean conception of ‘differance’, the spatial framework holds that everything exists in relation. For Derrida, differance (specifically written with an ‘a’) constitutes a conflation of the double meanings inferred by the French verb ‘différer’: difference and deferment. The definition of any word, Derrida asserts, is by necessity based in an infinite series of deferred meanings; each definition, being as it is based in language, requires further definition, and as such the structure of self-identical presence is a façade, leading only to endless postponement. Nothing can ‘Be’ itself in language without reference to everything else which exists around it, and as such it can be said that ‘presence’ is therefore not defined by its own positive qualities but is instead delineated through a relational, scaffolded structure of difference, deferment, ‘differance’. The singular point of presence we might expect to find at the centre of the haze of definitional relation is instead revealed to be a point of absence; an apertura.

The third and final ‘step’ in the proposed hauntological methodology is perhaps the most crucial: the act of articulation. The apertura is, in its most basic sense and at least initially, both experiential and internal, and its perception relies on our own individual preoccupations: due to the facts of my own life, I might notice an absence which someone else does not, and vice versa. Individual, affective relation between the self and the world becomes a cornerstone of the experience of the apertura and is therefore key to its functioning; but this must be articulated in order to come into its proper being as a non-present presence.

For example: in the introduction to his book Ghost Image, Hervé Guibert recalls in laborious and loving detail a photoshoot with his mother in which, after loading the film into the camera incorrectly, he had unknowingly produced only a set of blank images. He describes the shared feeling of grief at the loss not only of the images themselves, but of a profound mutual experience which the photographs might have evidenced. He then states, however, that the text of Ghost Image would “not have existed if the picture had been taken.” For Guibert, this empty presence of the image prompts new knowledge and creation despite its non-existence: the absence of something can be a conduit to presence, and the loss of an image, of a spatial and temporal relation, once documented and now gone, can be a bereavement so acute that a thousand conjurations of speech and text must follow it, and can only follow it. The apertura is an empty presence which drives us, by necessity, to an act of description which retroactively actualises its existence.

“But in order to inhabit even there where one is not, to haunt all places at the same time, to be atopic (mad and non-localizable), not only is it necessary to see from behind the visor, to see without being seen by whoever makes himself or herself seen (me, us), it is also necessary to speak.” I love that one. You’ll love it too. And I have to tell you: it feels good to speak. I don’t meet so many good listeners, but you’re perfect. Quiet and kind, with all that listening and looking!

Derrida’s prose at end of Specters of Marx reflects, with a gentle sense of debt and several references to the question of justice, hauntology’s potential as both “active and passive, an an-identity that, without doing anything, invisibly occupies places belonging finally neither to us nor to it.” All ‘this’, Derrida writes – meaning ghosts, hauntology, the specter; the figure of an absence which demands engagement – “this comes back, this returns, this insists in urgency, and this gives one to think”. He ends Specters with a question, which I will reproduce here in full:

“The phenomenology of the poetic imagination allows us to explore the being of man considered as the being of a surface, of the surface that separates the region of the same from the region of the other. It should not be forgotten that in this zone of sensitized surface, before being, one must speak, if not to others, at least to oneself.” That’s Bachelard. I really like that part.

I wonder if they’ll notice. Will they care, even? Probably not. Twelve paintings a week. Fifty, maybe more, for each film! They won’t notice. I wish they’d notice a little bit. Friz might like it, even. Maybe not. I miss mural painting. Maybe.

To take this idea of speech further and to state the point even more incessantly, we can say that an act of description also requires an act of revisitation; loss can only be described through revisiting its circumstances and articulating the space left behind. This I have shown already in recounting stories of my walks past my first childhood home and the drive to return as shared by others. In revisiting, the acts of noticing, returning and describing become entwined, through the process of articulation and re-articulation, into what I have come to think of as a hauntological writing practice. Somewhere between fictional and factual, between personal and theoretical, hauntological writing is undertaken simultaneously as a demonstration through usage and as a tool for investigation; it evidences itself as it takes shape. The empty space where my mother’s childhood home once stood is a personal and internal point of apertura, and so I revisit its image in order to pull out and describe its hauntological qualities. It has both temporal and spatial hauntological import: the empty space is haunted both by my sparse knowledge of its past and by the physical, spatial gap which helps to make this temporal and informational absence more visually poignant. These deductions might be made internally, and can be kept internal if we wish, but the hauntological frameworks and relations only become actualised through the process of revisitation and articulation; without this, the empty lot is just an empty lot, and nobody knows or cares that in-between the grass and the fences, just up from the concrete slabs, used to be the place where my mother learned to walk, read, and speak.

(These are in my town.)